Advanced issues

Search: Tackling the Boolean NOT

Search Visualiser can be used to solve a long-standing problem in search, namely finding documents that are not just about the usual suspects.

Composing and checking texts

Search Visualiser can be used when creating large texts, such as PhD theses, manuals, textbooks, and fiction, to check for structure and balance and distribution of topics across the text.

Comparing texts across languages and cultures

The visual/auditory nature of Search Visualiser enables comparison of rhetorical structures across languages and cultures.

Tackling the Boolean NOT

A long-standing problem in search is finding documents that are not about the usual suspects. For example, if you are trying to find documents about sources of green energy other than wind, wave and solar, you can't simply tell your search engine to ignore any documents that contain any of those terms via a search phrased along the lines of “green energy NOT wind NOT wave NOT solar”. (The precise syntax will depend on the search engine.)

The problem is that documents about other types of green energy will probably also mention wind, wave and solar. So, if you exclude documents that mention those usual suspects, you will probably also be excluding precisely the documents that you want to find.

Search Visualiser lets you sidestep this problem, by using significant absences within well-structured documents.

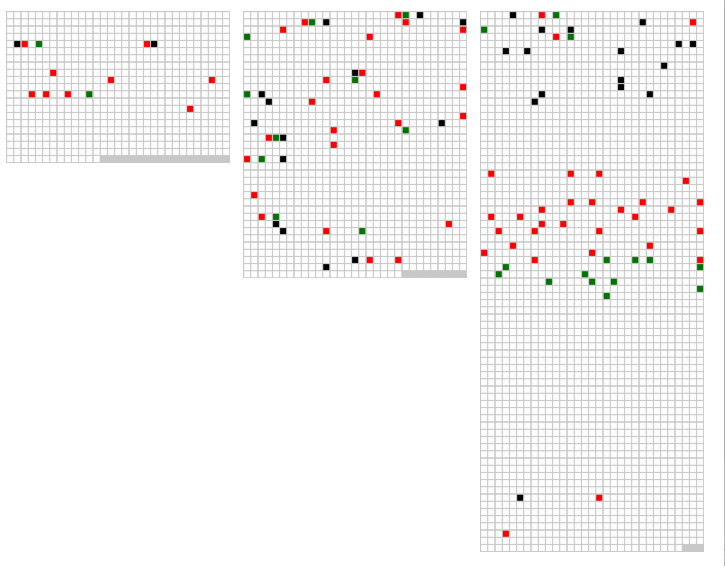

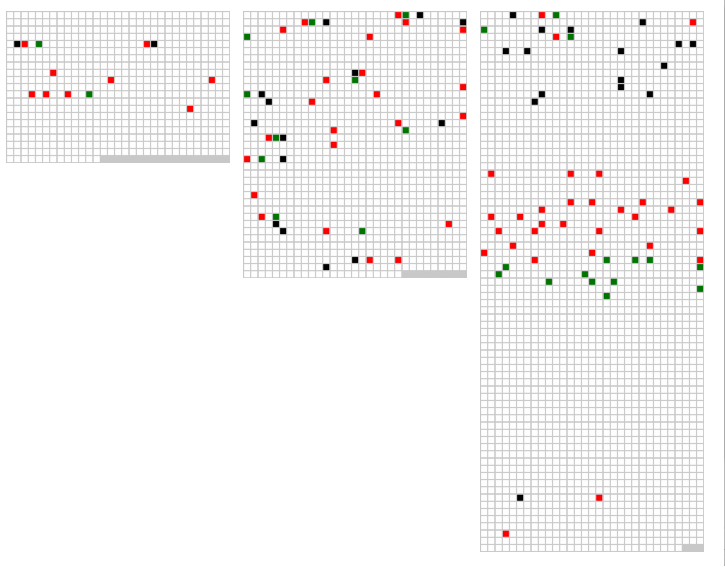

In the search results for wind, wave, solar below, the third document has a band of black keywords, then a gap, then a band of red, then a band of green. This implies that the gap contains text about a different form of green energy, which is in fact the case; the gap turns out to be about tidal power.

Composing and checking texts

When creating large texts, such as textbooks and theses, it can be difficult to keep track of overall structure and of themes.

Search Visualiser can help by showing the distributions and frequency of terms across a text. This is useful both for the obvious issues of balance and structure, and also for more detailed features such as ensuring that an important concept is flagged early on in the text, to let the reader know what will be coming later.

This is visible in the example opposite, of a search on the keywords wind wave solar.

All three documents mention those three concepts very early on, telling the reader what to expect.

The first document is then mainly about the red keyword, with just one mention of green. The second document has all three keywords mentioned frequently, intermingled with each other, without a clear thematic structure.

The third document has a short opening section which includes repeated mentions of all three keywords.

It is then cleanly divided into sections about each keyword, with a significant absence between the black and the red keywords, where it discusses tidal power.

There is then another gap, taking up almost half the document.

Near the end, there are two mentions of the red keyword and one mention of the black one, in what looks like a summary section.

This visual representation shows clearly the thematic structure within the third document, in a way that helps the reader see the overall thematic shape.

Comparing texts across languages and cultures

Search Visualiser can be used to show structures within texts across languages and cultures.

The image opposite shows mentions of two main characters, Holmes (red) and Drebber (green) in Conan Doyle's A Study in Scarlet. At first, only Holmes is mentioned. Drebber then makes an appearance, and is as prominent as Holmes around the half-way point of the story. The second half of the story hardly mentions Holmes, and is largely about Drebber.

This reflects Conan Doyle's use of the story-within-a-story structure in the second half of the text. Conan Doyle uses this structure within several, but not all, of his texts.

Representing texts visually in this way makes it possible to compare some features of texts directly, such as use of narrative structures, across languages and cultures, without needing to translate those texts.

This has considerable implications for post-colonial studies of texts across languages and cultures.